This poster makes the film look so sleazy. This poster makes the film look so sleazy. As a classic noir fan-scholar, I look for women’s voices behind the screen. One of the few is director Ida Lupino. The Hitch-hiker (1953) is her most obviously noir film, telling the tale of two average guys (Edmund O’Brien and Frank Lovejoy) who find themselves at the mercy of a psychopathic escaped convict (William Talman at his finest). It’s a great B noir thriller: without subtlety or nuance but an exciting ride. The rest of Lupino’s films are probably best described as social dramas, from the first Hollywood picture about rape directed by a woman (Outrage, 1950) to the first dealing with bigamy (The Bigamist, 1953), starring Edmund O’Brien as the unlucky fella, Lupino herself and Joan Fontaine (‽) as his two wives, and Edmund Gwenn as an annoying investigator. I’m learning, however, that several other of Lupino’s films can be considered at least noirish. The Bigamist is sometimes discussed as noir for its underside-of-the-American-Dream emphasis and crime, for instance. But to that I’m definitely adding the Hard, Fast and Beautiful! (1951), not the least of which for its absurd title and its exclamation point. The film is loosely based on the John R. Tunis’s novel American Girl (1930), which is about America’s first female tennis celebrity, Helen Wills Moody. (If you haven’t heard of her, she’s worth reading about. Eight Wimbledon wins!) For Lupino, the “true story” is fodder for romance, scheming, and deception. We have what Hollywood of the post-war era would call a “weak” father figure; an obedient, talented, and perky daughter (Sally Forrest – also the star of Lupino’s Never Fear (1950), which I’ll see and review soon!); and the controlling mother determined to get rich (Claire Trevor). The casting of Trevor in this part is noir gold on its own. She’d already won the Academy Award for her portrayal of Gaye Dawn in Key Largo (1948) and played the black widow lead in Murder, My Sweet (1944). She’s also known to noir fans for central roles in Crack-up (1947), Raw Deal (1948) and my favorite of her pictures, Born to Kill (1947), in which she plays a psychopath to Lawrence Tierney’s sociopath and the two actually sizzle. The picture also features Elisha Cook, Jr. and Esther Howard at their best. I put off watching Hard, Fast and Beautiful for a long while because I though a tennis movie would be dull. (While I was working on my book on gender in the films of George Cukor, I learned that I dislike Pat and Mike (1953), for example, a quite different tennis film of the same era featuring annoying battle-of-the-sexes rhetoric throughout). Lupino’s film is far from dreary, however. We watch as our young heroine Florence -- of humble, middle-class beginnings – develops her tennis skills and falls in love with regular guy Gordon (Robert Clarke). He works a menial job at the local country club (for now) and gets Florence in. Mom Millie (Trevor) is thrilled at this access to the upper-class set, which husband Will (Kenneth Patterson) cannot provide. Millie has already (or always already) given up on Will and seeks the wealth and privilege she feels she deserves through her daughter. The manipulation of Florence and Millie’s ultimate fate (shown in the film’s final scene, which I won’t give away beyond that) make this film definitely worthy of the descriptor “noirish,” even if there is a happy ending for Florence and Gordon. Sadly, that blissful heteronormative closure comes at the cost of career, for happy housewife and mother is Florence’s ultimate goal, much to mom’s chagrin. Even scheming manager Fletcher Locke (Carleton G. Young) lightly moves on to a new, younger female player to build another star. Given the era and its gender norms, a little more might be said. The contrast between Florence and Millie is intended to reflect a good/bad, virgin/whore binary, and champion those who can be happy with everyday, middle-class lives. (Lupino also returns the rape-scarred protagonist of Outrage to her ignorant “nice guy” fiancé at the film’s conclusion, although she does not show the reunion on screen.) But there is also a potential feminist argument for the ambitious wives-gone-bad here. Millie has not been educated for a career nor attempted one because she’s opted for what the culture tells her is best: marry a man and stay home. This drives her to overinvest in her daughter, to get her daughter to live the life she wishes she could have, a life of fame and fortune. The ambition is too high, but the idea that suburban women of the post-war era have thwarted goals will come to haunt us soon, as reported by Betty Friedan in The Feminine Mystique. I also see this pattern in late noir Crime of Passion (1956), in which Stanwyck’s Kathy Doyle actually has a job, writing an advice type column for a newspaper. She gives it up to marry police detective Bill (Sterling Hayden), but soon finds he lacks the ambition to advance in his career, and she is miserable in the dull life of the suburbs. She thus overinvests in him (because they don’t have children to push), trying to manipulate his career behind the scenes through sex with his superior, Tony Pope (Raymond Burr). She thus goes from good/virgin to bad/whore, and a feminist position might critique the culture that necessitates such choices. Whatever your perspective on the sexual politics of the 1950s, I do recommend Hard, Fast and Beautiful! This genre-bending B classic is definitely worth 78 minutes of your time – and easy to find free online.

0 Comments

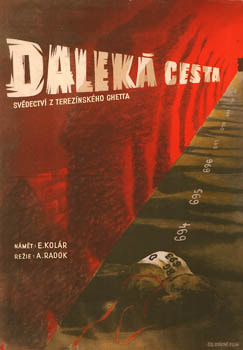

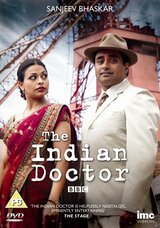

The Distant Journey (Daleká cesta), 1949, dir. Alfréd Radok Back to Holocaust cinema and post-war Czech films. I find The Distant Journey fascinating, even more in conceptualization and production context than in the actual film. Screenwriter/Director Alfréd Radok was what the Nazis would call a Mischling, born of a Jewish father and Catholic mother. While we Jews conceive heritage through the mother, for so-called Aryan science Jewishness was about race not religion, and any Jewish heritage in parents or grandparents would do for identifying one as at least partly Jewish. That Radok was baptized didn't matter when it came to the Nazis. Radok worked in theaters in the early 1940s, but was forced out because of his heritage. In 1944, he was sent to Klettendorf labor camp, from which he managed to escape with the help of an allied air raid in January 1945. HIs father and all paternal family members were murdered. To make a film abut the Holocaust so soon after his experiences and losses speaks of its importance to Radok. And the film he made is equally important, especially for its stylistic choices, including the mixing of historic footage of the Nazis and excerpts from Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will with a dramatic, fictional tale of a Jewish doctor and her non-Jewish husband. The film even presciently uses as screen-in-screen style representation, as the fictional story images shrink to a small box on the lower right of the screen as Nazis march or Hitler speaks in the main frame. Then the box expands and the narrative takes over again. Also significant was its censorship by Stalinism implemented in Czechoslovakia soon after release. As the picture-in-picture element helps us to put the specific tale of the fictional central couple against the Nazi war machine, the film's pace helps us see the slow but sure impact of antisemitic laws and the "Final Solution" on the Jewish people, including and, by implication, beyond the film's characters. Another powerful choice made by Radok is the refusal to show blood or other evidence of violence within the film. Physical terror is represented psychologically, such as the scene of a suicide in which we neither see nor hear a man jump from his window to his death. Instead, we hear a cry in reaction and know its cause. For more about the film's history and significance, you might wish to read this English language Central Europe Review article "Living with the Long Journey." (Thanks to Czech scholar Milan Hain for this recommendation.) Ultimately, I enjoyed Diamonds of the Night more than The Distant Journey as a viewing experience, but with the background knowledge I now have, I find them equally important to see, each in its own way.  The Indian Doctor - Season 1 (+ first episode of Season 2) SPOILERS I thought I'd give this BBC show from 2010-2013 a go as something Welsh but different from the Welsh crime dramas I've watched and sometimes enjoyed. (Definitely a choice inspired by the corona virus and stay-at-home orders.) I worried over potential ghastly racist humor at the premise of a doctor and his privileged, snappish wife from big-city India opting to move to small-town Wales. But I also considered the potential for some confrontation in showing the "foreigner" as the kind figure to teach working-class whites about issues of difference. That it's listed as a drama not a comedy-drama or sitcom helped, as did the decent IMDb ratings and reviews. In I dove! I should've remembered that I rarely agree with the ratings on IMDb. Sitcom-level dialogue and acting and a predictable plot trajectory were the order of the day throughout the first season. Incredibly beautiful wife Kamini (Ayesha Dharker) loathes everything, from the tiny apartment above the shabby practice to not having servants to make her tea. She calls the capable young receptionist Gina (Naomi Everson) "girl," demands to go to London, and even when her heart melts a little over trouble-making child Dan (Jacob Oakley) -- in part because her own daughter with the titular Doctor Prem Sharma (Sanjeev Bhaskar) died...somehow -- it doesn't add much depth to the character. The neighborhood gossips are equally one-dimensional, as is Season 1 villain, cartoonishly named mine owner Richard "Dickie" Sharpe, played by Father Brown himself, Mark Williams (though I remember him best as Peterson in Red Dwarf and others may recall his turn as the Weasly patriarch from the Harry Potter films). That this "Dick" turns out to be impotent and simplistically malicious is highlighted by the machinations of his absurdly randy red-headed wife Sylvia (Beth Robert), who says she longs to have a child but mostly likes to put on fancy dress and 60s wigs and lord it over the commoners. There's also a subplot in the first season in which Gina falls for rock-n-roll singer wanna-be Tom (Alexander Vlahos), then gets pregnant and fears she'll be thrown out of her house by her judgmental town-gossip grandmother, as well as a hunt for Dr. Sharma's predecessor's diary, which will out the evil doings of DIckie Sharpe. Oh, and Tom's step-mother Megan (Mali Harries) has a crush on Dr. Sharma who has ambiguous feelings but mostly warm friendship feelings with her. All in all, the main tension over the mistreatment of the miners takes a back seat to soap opera antics which generally center on babies. Thus, race and class issues are addressed predictably and superficially and serve the purposes of predictable and superficial melodrama. And so much focus on babies turns the 1960s into a one-dimensional anti-feminist mush. The Sharmas decide to stay in town after all, the single pregnant gal is not rejected by grandmother or boyfriend...maybe, and Kamini gets a part-time substitute child to share with the alcoholic superficial socialist union leader. Coda: Against my better judgment, I watched the beginning of the first episode of Season 2, only to find that The Indian Doctor had fully become a generic light dramedy of familiar characters and who-cares plot. Couldn't make it through the episode. My reviews for this post are both series I watched via Netflix. One for general interest, the other for Holocaust studies. 1. Murder Maps, Seasons 1-3 (2015-2017) [12 episodes] This BBC program(me) tells the tales of some of England’s most notorious murderers. The first three seasons move historically from the 19th century to the 1950s. What makes it interesting to me is how it talks about the development of investigation strategies and social issues alongside the gory details of killers from George Smith, the bigamist who murdered multiple wives in their baths, to John George Haigh, the “Acid Bath Murderer.” The show is slow-moving and superficial, repetitive in images and words, but I enjoyed seeing forensic science develop alongside attitudes toward gender, class, criminality, and the death penalty. Bored? Give it a go. 2. Charité at War (2019) [6 episodes, in German with English subtitles] ~LITE SPOILERS AHEAD~ This German production is actually a second season of the series Charité, about the famous Berlin hospital. The first season (which I haven’t watched) takes place in 1889, while the second takes place in 1945. I very much appreciate the focus on the characters, mostly doctors and nurses who challenge the simple binary of perpetrator/victim. By this time in the war, the Jewish hospital staff and patients are long gone. There are loyal staff, proud of their “Aryan” designation, but most of the characters we meet are sick of Hitler, sick of Nazi policies, and sick of war. The program intersperses fictional characters among famous historical figures, including the pioneering Dr. Ferdinand Sauerbruch and would-be Hitler assassin Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg. I like that the series focuses on children at the hospital, with special attention to some doctor and nurses’ naivete regarding the moving of children with mental and physical disabilities to “safer” facilities out that are actually transports to death camps where they will be gassed. Also addressed is Paragraph 175, the law against homosexuality, ramped up by the Nazis to include such choices as castration or imprisonment (sometimes in concentration camps). How these important issues are addressed is more problematic for me, as this relies almost entirely on the mode of melodrama. We meet a couple in which the husband is a doctor, second only to the children’s hospital’s chief of staff. His wife, who begins the series quite pregnant, is studying for her medical degree at the Charité. When she gives birth, they find their baby might have a disability. The melodrama in this personal crisis played out within Nazi efforts to rid the world of what Hitler called “useless eaters” goes into high gear. Similarly, we meet her brother, a soldier who visits his sister and stays on at the hospital, continuing his studies in medicine and avoiding the front for as long as he can. He turns out to be gay, and then we start the lesson on Paragraph 175 through this personalized lens. I’m also less than thrilled by the portrayal of villainous Nazis in the show. Two characters stand out from the more complex bystander types. One is the female zealot stereotype Nurse Cristel, with her blonde hair, blue eyes, and big mouth. She spies and snitches and earns retribution. I see no way not to relish the carefully filmed moments of her humiliation and her ultimate fate. The other villain is the male sadist type, head of psychiatry Max De Crinis (based on a real individual). He is slimy and scheming and positively delights in condemning soldiers who may have wounded themselves to get off the battlefield. Ultimately, I saw some areas of focus I have not seen in other films or series, and it is good that such work is coming out of Germany. Less Hollywood-style emphasis on melodrama and Nazi stereotypes would have been welcome, but I’m definitely glad I watched it. Recommended.  Tennessee finally has a shelter-in-place order, so it's time to blog!Over the past weeks, I've been watching new (to me) films in two primary categories:

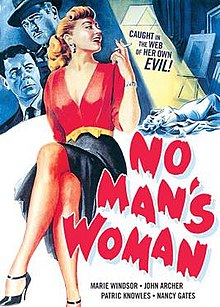

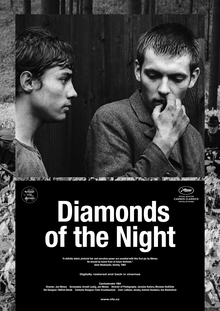

Category 1: No Man's Woman (1955) is a very-B noir thriller (sans noir cinematography). Directed by Franklin Adreon. It's only truly noteworthy element is the presence of Marie Windsor as the spider woman at the heart of a very thin web. Windsor sports a bumper bang and tight sweaters and gives much face as she runs a successful art business while blackmailing her husband who seeks a divorce, cheating her infatuated business partner, and attempting to seduce young hunk Dick *snicker* (Richard Crane), who is engaged "good girl" employee Betty (Jil Jarmyn). The script is thin, the acting thinner, and the mise-en-scene missing and presumed irrelevant. But it was a fun way to spend 70 minutes while sheltering in place.  Category 2: Czech Holocaust films are high on my currently list of to-watch films. I have very little knowledge of the history of either the country (in various forms), political movements, or the Nazi occupation. I'm beginning to learn, which is important to understanding the films and their historical, cultural, and artistic importance. I began my filmic introduction with Diamonds of the Night (Démanty noci, 1964). The film has few words, which is good because I couldn't find a version online with subtitles (though I've now remedied this by purchasing the Criterion edition). This 67-minute tale of two boys on the run after escaping a train headed for a concentration camp was director Jan Němec's first film, based on an autobiographical novel by Arnošt Lustig. Realism based in following the boys via hand-held camera as they run through the forest, swamps, and rocky terrain has a powerful impact on the viewer, bringing us close as we hear their panting breath and feel their desperation. In this way, the film avoids the trap of melodrama seen in so many Holocaust films or the peephole style that can objectify victims. Nonetheless, it is not just a tale of escape and adventure, for we do get inside one of the boy's minds to see flickers of his recent and more distant past. We also see multiple versions of his experiences as they flit through his mind, and we cannot know which is true. Some critics call this element surrealist. It happens with particular impact as one of the boys steals from a farm: does the woman give him bread or does he hit her and take it, leaving her (dead?) on the floor of her kitchen? Such a technique is also used at the film's conclusion,so we cannot know the immediate (or ultimate) fate of the boys. In writing this review, I used the Wikipedia entry to get spellings right and learned something new I also want to share. In the film, we do not know who these boys are, only that they were put on a train to death and that they escaped and fled. We don't know if they are Jewish or of another victim group or petty criminals the Nazis simply decided to transport to the camps. The characters are only named First Boy and Second Boy in the script (and a voice actor was used for the Second Boy, who is the only one of the two with (minimal) dialogue in the film. The Second Boy, Wikipedia states, was a Roma railway worker the director cast after seeing him in a documentary. (FYI: Roma = "Gypsy" - a group identified by the Nazis as racially inferior and "asocial," targeted for extermination but with less purposeful, formal organization and zeal than the Jews). Reviews say director Jan Němec (whose surname is common and also seems to mean either "German" or "mute"!) particularly admired the films of Luis Buñuel. I'd call this film a must-see for anyone invested Holocaust cinema or film technique. |

AuthorElyce Rae Helford, PhD Archives |