AN INTRODUCTION TO FILM NOIR

LINEBAUGH LIBRARY SERIES / SPRING 2018

February 1, 2018: FILM NOIR'S ORIGINS

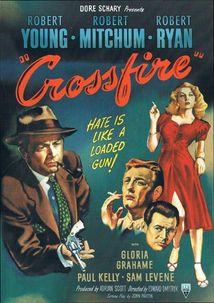

Screening: Crossfire (1947)

What is film noir?

Classic American film noir cycle = 1940s-1950s

Not called “film noir” (black/dark film – dark in style and content) until the 1960s

World War II in many ways led to what we call “film noir”:

- Cycle = group of linked films within an era

- Genre = type of film with specific content (characters, plots, themes)

- Style = formal/aesthetic elements of film

Classic American film noir cycle = 1940s-1950s

Not called “film noir” (black/dark film – dark in style and content) until the 1960s

World War II in many ways led to what we call “film noir”:

- desire for films that reflected American cultural anxiety, especially after Pearl Harbor

- extension into the 1940s of Depression-era interest in hard-boiled fiction, radio detective series, True Crime magazines, etc.

- loosening of the Motion Picture Code to allow more sex and violence in film

- draft of young men

- more film roles for older men (shift away from romance)

- more active roles in culture and in film for women (e.g. femme fatale)

- influx of directors, writers, cinematographers, and composers fleeing Nazi Germany

- German Expressionism (visual expression of internal emotional states)

- French poetic realism (darkness in style and emphasis on “unsavory” subjects)

- economics: studios needed to make movies cheaply, leading to film noir aesthetic

MARCH 1, 2018: THE NOIR LOOK

Screening: The Big Combo (1955)

Noir films are generally dark, both in tone and style. Last month, we looked mostly at film history (the "why" of film) and content (the "what" of film). This month, we turn to form (the "how" of film), particularly lighting, a vital element of noir style.

Here are a few central lighting elements to the noir look:

While these cinematographic techniques were intentionally used, we should also remember that economics were also influential in creating the noir look. Using less electricity meant lower costs. And darkness could hide cheap or reused sets.

There are many great introductory videos on film lighting, and because of its heightened style, film noir is one of the best styles through which to learn about lighting.

Filmmaker IQ's "The Basics of Lighting for Film Noir: https://youtu.be/jsmVL7SDp5Y

Here are a few central lighting elements to the noir look:

- Low-key lighting = a style that accentuates contours of subjects; puts areas in shade while a fill light illuminates shadow areas for contrast

- Chiarascuro = highlighted patterns and contrast of light and shade; the effect of low-key lighting

- Dutch angle/tilt = using a tilted camera to create feelings of anxiety in the viewer

- Choker shots = extreme close-ups that serve to display strong or distorted emotions

- Cookies = cut-outs placed over lights to create an effect across a character, such as venetian blinds (also see Gobos)

While these cinematographic techniques were intentionally used, we should also remember that economics were also influential in creating the noir look. Using less electricity meant lower costs. And darkness could hide cheap or reused sets.

There are many great introductory videos on film lighting, and because of its heightened style, film noir is one of the best styles through which to learn about lighting.

Filmmaker IQ's "The Basics of Lighting for Film Noir: https://youtu.be/jsmVL7SDp5Y

APRIL 5, 2018: THE FEMME FATALE

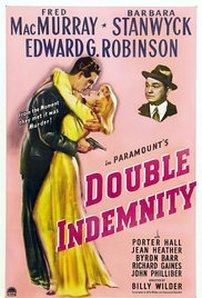

Screening: Double Indemnity (1944)

Building from the focus on the history of film noir as it relates to WWII and the importance of the look, we can return more fully to exploring content through character types, particularly the femme fatale.

Common character types in noir:

The femme fatale did not suddenly emerge in film noir. She is related to the figure of the vamp of the silent film era, the dark seductress figure. Unique to the WWII-era, however, is her relative power within the films. Femme fatale roles are some of the best and biggest women's roles Hollywood had to offer in the 1940s and 50s, combining sex appeal, strength of will, active presence (vs. a beautiful object to be ogled), and great dialogue.

Given the Motion Picture Code (how Hollywood policed itself so the government wouldn't), the femme fatale was not allowed to get away with such a challenge to social norms. (Plus, she often acted both unethically and illegally.) The femme fatale had to be punished by the end of the picture to satisfy the censors. Generally, this meant death or at least imprisonment, although on rare occasion she could (also) change her ways and become marriageable (another way to control her norm-challenging behavior).

We will watch Barbara Stanwyck embody the femme fatale to typed perfection in Double Indemnity. Worth noting is that Stanwyck played just about every noir female type we can name:

Common character types in noir:

- the hard-boiled detective (often an anti-hero)

- the ill-fated everyman

- the good wife (helpful woman)

- the femme fatale (or spider woman)

The femme fatale did not suddenly emerge in film noir. She is related to the figure of the vamp of the silent film era, the dark seductress figure. Unique to the WWII-era, however, is her relative power within the films. Femme fatale roles are some of the best and biggest women's roles Hollywood had to offer in the 1940s and 50s, combining sex appeal, strength of will, active presence (vs. a beautiful object to be ogled), and great dialogue.

Given the Motion Picture Code (how Hollywood policed itself so the government wouldn't), the femme fatale was not allowed to get away with such a challenge to social norms. (Plus, she often acted both unethically and illegally.) The femme fatale had to be punished by the end of the picture to satisfy the censors. Generally, this meant death or at least imprisonment, although on rare occasion she could (also) change her ways and become marriageable (another way to control her norm-challenging behavior).

We will watch Barbara Stanwyck embody the femme fatale to typed perfection in Double Indemnity. Worth noting is that Stanwyck played just about every noir female type we can name:

- Femme Fatale: Double Indemnity (1944), The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946), The File on Thelma Jordon (1950),

- Good wife/Victim: The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947), Cry Wolf (1947), Jeopardy (1947),

- Morally mixed role: Sorry, Wrong Number (1948), No Man of Her Own (1950), Clash by Night (1952), Crime of Passion (1957)

May 3, 2018: The End of an Era

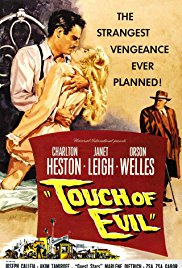

Screening: Touch of Evil (1958)

Generally considered the final film of the classic 40s-50s noir cycle, Touch of Evil is noteworthy for its content, style, production history, and reception.

Noir Content and Style

Historical/Production Context

Reception

Today

Noir Content and Style

- Thriller based on a Whit Masterson hard-boiled crime novel Badge of Evil

- Typed characters: morally upright cop, corrupt sheriff, gang/mafia, good wife

- Setting: moved from novel set in San Diego to Mexican-American border town; dark, exotic locales

- Extreme noir cinematography: looming, restless camera; tilted, disfiguring angles; forceful shadows

Historical/Production Context

- National mood grew optimistic with expanding affluence and less apocalyptic political/military concerns

- Media shifted to focus on positive and trivial, e.g. sitcoms and new popular film genres

- Welles had been in Europe during the 1940s height of noir and did not see it had tapered off in popularity

Reception

- Test audiences found the film dark and confusing; new editor made cuts and added scenes

- Film flopped in U.S. despite changes, but it was popular and praised in Europe

- Welles was fired and lost contract options for future Hollywood pictures

- Film was re-edited in 1997 based on a 1957 58-page letter Welles wrote to Universal to repair the damage

Today

- Extremes of style, production, and reception led to film’s label as bitter end to the classic noir cycle

- Contemporary critics praise the film’s style and atypical position on race (white as evil)

- Feminists critique the positioning of (white) woman as objectified pawn used to manipulate “good” cop